Nothing to See Here

What stories can we find in the AI-generated

descriptions of coronavirus stock photography?

(Glen Cary via Unsplashed)

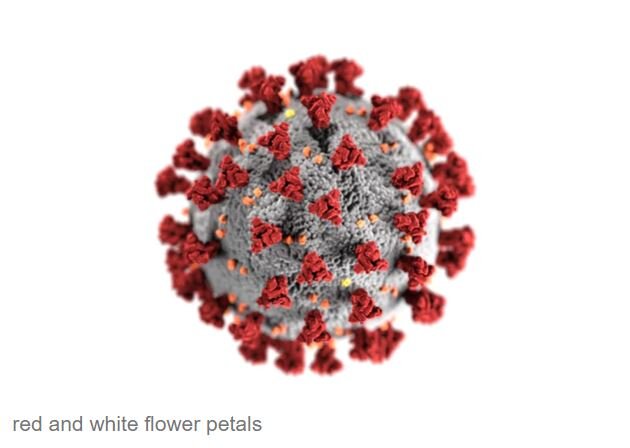

I was looking for covid-19 stock photographs when I saw it: the same image you’ve probably seen in countless news stories and blog posts about the novel coronavirus. It’s a simulated microscopic image, where the virus itself appears like a big white ball, with red triangles bursting forth from tiny antennae. It was simple enough for me to recognize. But the image classification engine was having a harder time of it. Struggling to define this strange new thing that has so disrupted our lives, it looked to its memory and found the closest description it had: red and white flower petals.

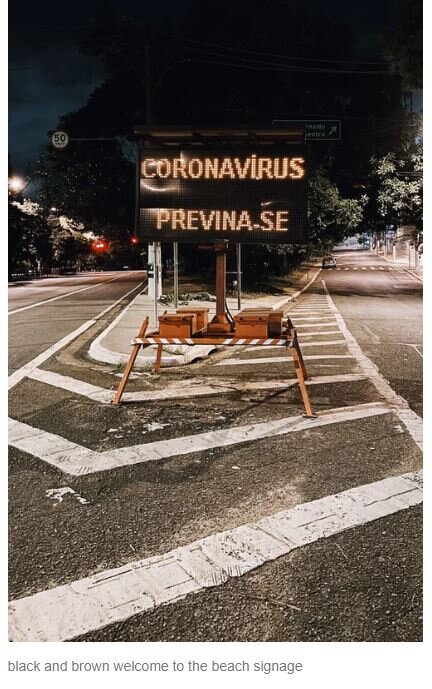

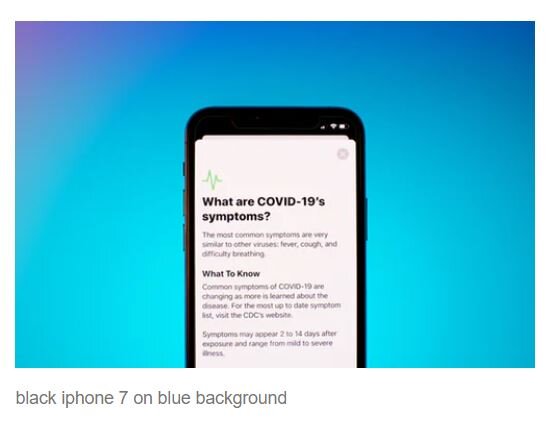

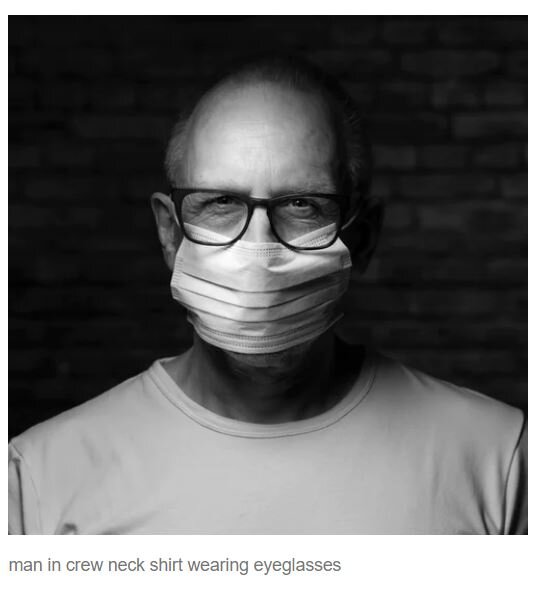

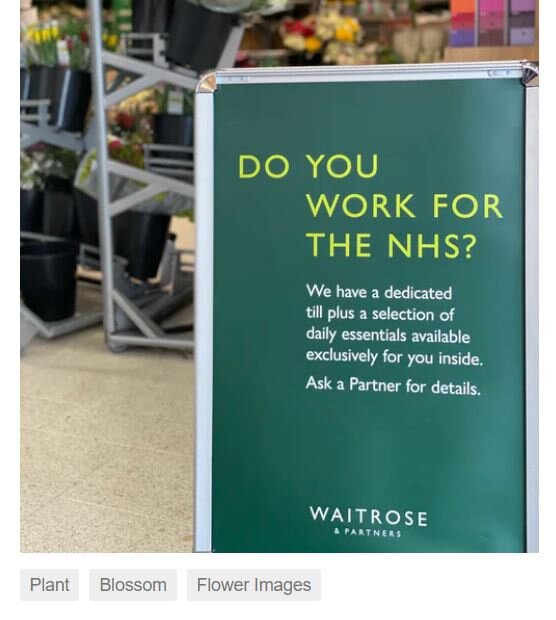

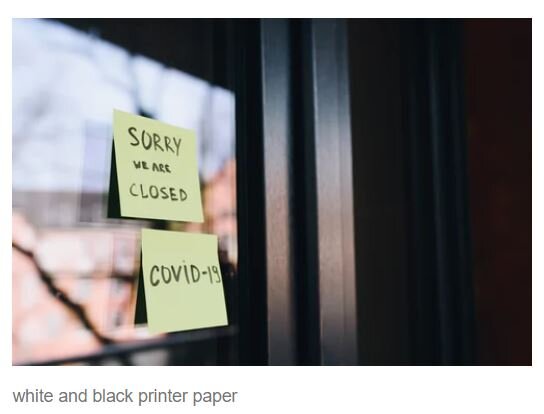

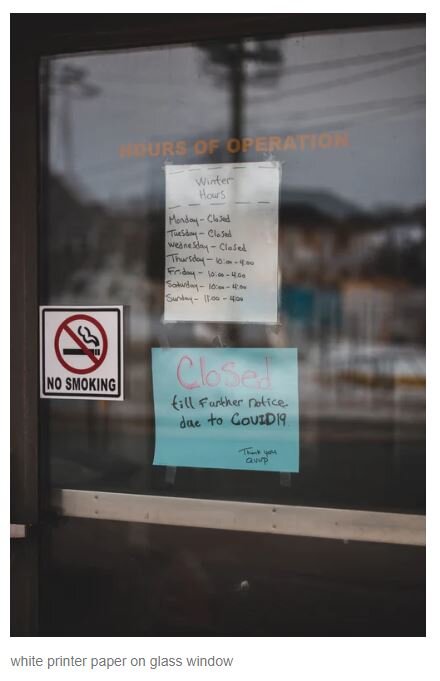

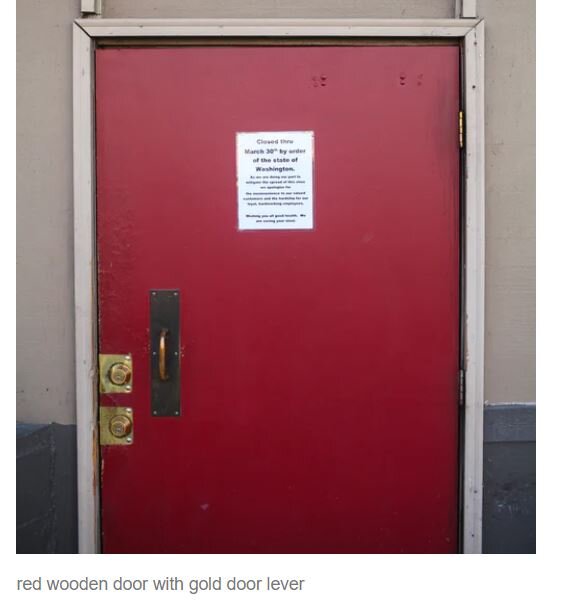

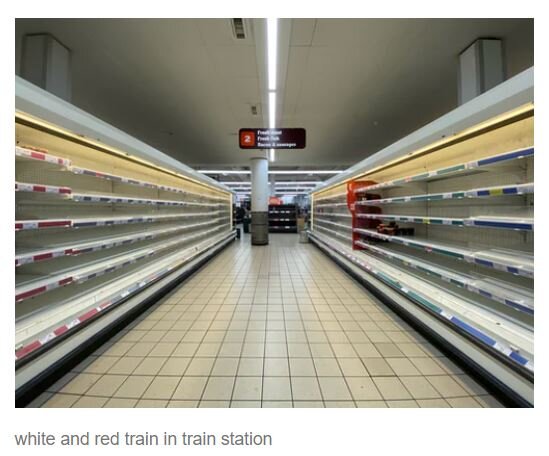

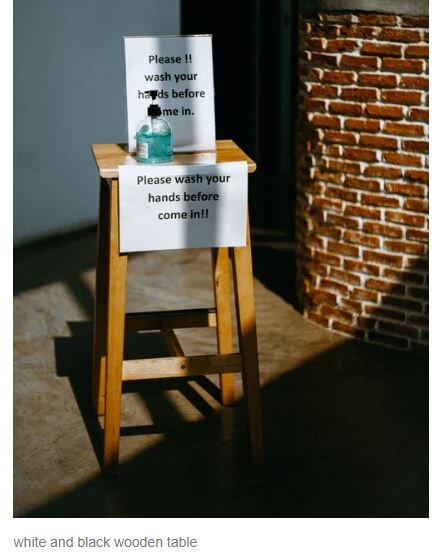

As I kept exploring, the emotional distance between the images and their descriptions was what you might expect. The machine is comparing symbols of a two-month-old reality with images from a world that could barely conceive of the phrase “global pandemic.” All the iconography of this new era is there in pictures — hand sanitizer, face masks, hand-written notes taped to the doors of shuttered businesses. But they were either unrecognizable to the machine’s reference library, or else their context was completely ignored.

The result is a poetic gap. The virus is reduced to a flower arrangement. There’s a dreamy, naive surrealism between what we see and what the sentence below it describes.

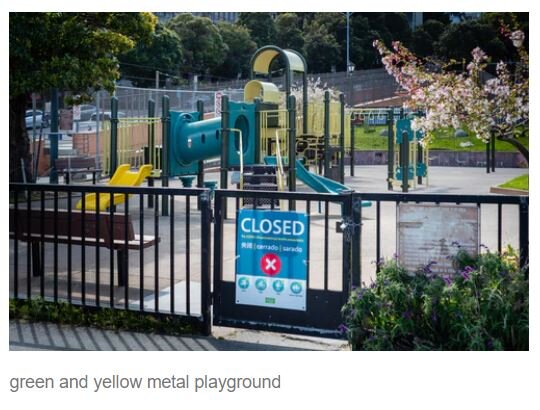

I selected a few of these images and present them below with the labels given to them by the machine. Each of these images was screen grabbed on May 3, 2020 and is otherwise unedited. Credits and links to the original photographers are below the gallery. (Use your left and right arrow keys to move through the images below).

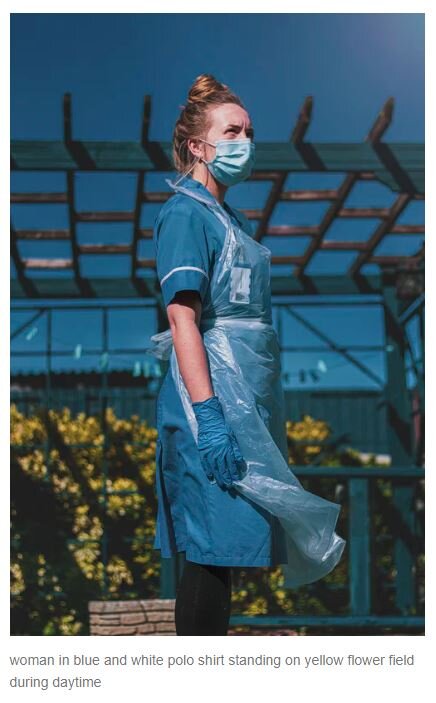

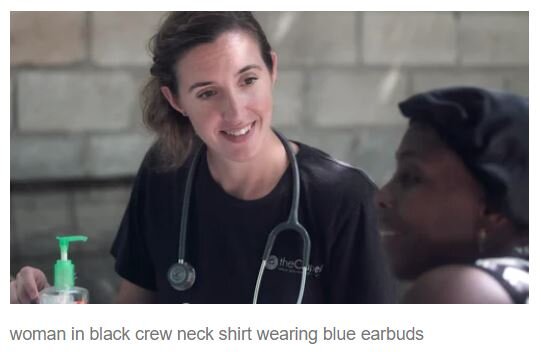

I see a nurse covered in scrubs and a face mask standing in front of a hospital; the machine simply sees a woman in blue, standing in a field of yellow flowers.

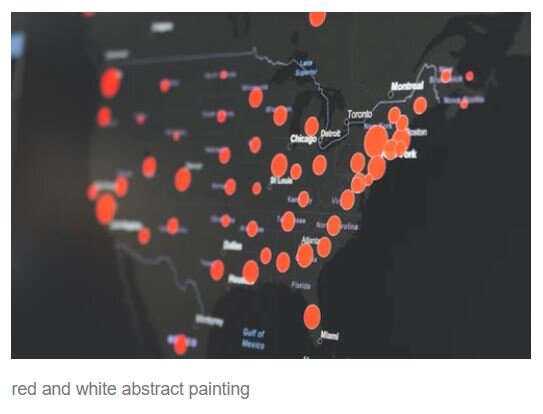

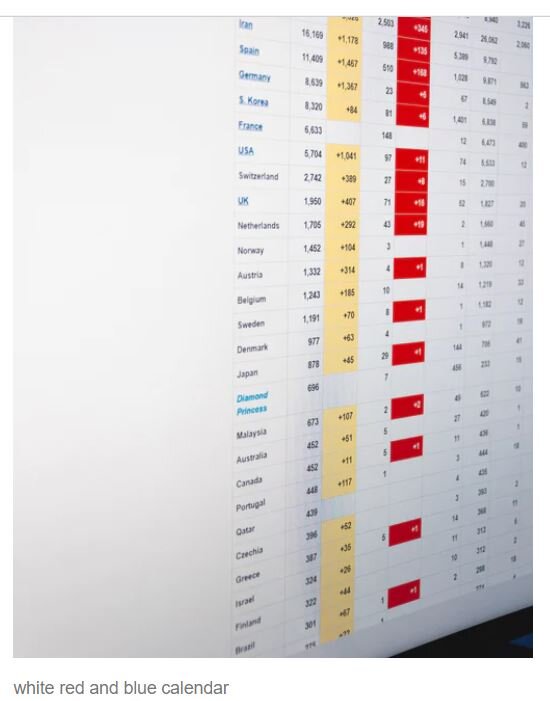

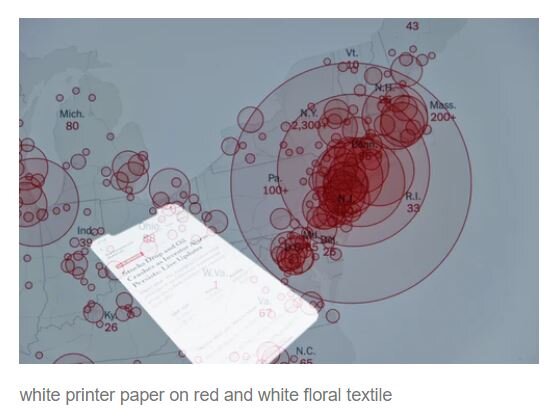

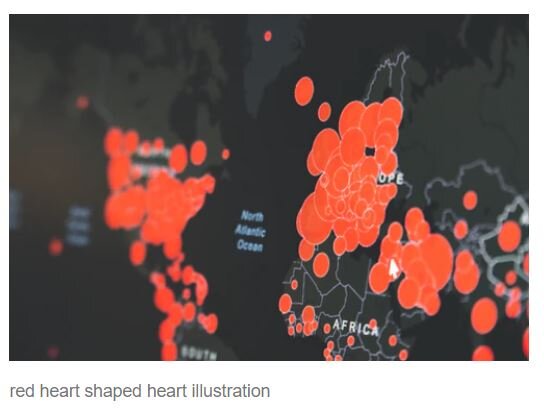

I see a data visualization of casualties, those familiar red circles obscuring Middle Eastern, American and European cities like pools of blood on black backgrounds. The machine sees an abstract painting. It describes another as a floral print on textiles.

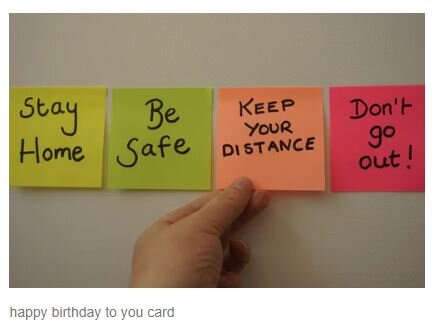

There’s an image of that old stock-photo standby, the post-it note with hand written messages. This one has four, spelling out the covid equivalent of slogans from the most boring revolution: Stay Home. Be Safe. Keep Your Distance. Don’t Go Outside. The machine labels it as a Birthday Card. (It happened to be my birthday).

Elsewhere we see signs on the doors of businesses who have closed their doors, messages full of uncertainty about when they might reopen. The sentence below it reads, “pieces of paper.” It’s not wrong. They are. It’s just that it isn’t the point.

There’s an old joke in which a doctor turns to Abraham Lincoln’s widow Mary Todd Lincoln, just after the presidential assassination inside the Ford Theater. In the joke, the doctor asks, “But other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”

The machine has its own version of the bit.

There’s no reason to expect them to do any different. I understand why this happens. What I didn’t understand is how caught up in it I would feel. In a world where we’re longing for the dull normalcy of January as if it were some kind of paradise, this all fell into a stark, confusing alignment with that yearning.

Maybe a piece of Mary Todd Lincoln wants to talk about the play. It would mean a world where the tragedy didn’t happen, or a world where she’d simply been able to forget it, for a moment: both impossible, but seductive dreams.

The labels on these images are gleeful in their denial, their weird insistence that there’s nothing to see in this photo of people in surgery masks on an empty city street: it’s just two people.

That sign marking 1.5 meters of social distance on the sidewalk? Nothing to see here. Just a sidewalk. Playground with a giant, menacing “closed” sign on the gate? Nothing to see here. Just your average playground.

The algorithms describe these images strictly by references to our lost, quote unquote “normal” world, literally incapable of generating the kind of vocabulary needed for this messy reality.

You could draw some critical insights about gaps in attention and context between humans and our algorithms. But I am struck by how they show us the world through a pre-covid lens: not nostalgic, not that sense of being away from home, but solastalgic: longing for a home that is leaving us.

The gap lets our “normal” past drift into the present, but the result is a jolt. It only highlights the contrast between where we are now and where we were then, sneaking a tiny emotional itch into the everyday world of stock photographs.

Max Ernst wrote about his dadaist collage as the “confrontation of two or more mutually alien realities on an obviously inappropriate level - and the poetic spark which jumps across when these realities approach each other.” In the case of these machines, the code is working fine, making an analysis, but the algorithms haven’t caught up to our context, or simply don’t care. That gap is where the poetic spark leaps; the punctum: the accident which pricks me.

We ponder the distance between the the systems we create and the world in which those systems take action. We build a library, and then everyone learns another language. How might we think about the decisions of these machines if we knew they were meant for another world? And how might we design machines that tell us which world they belong to? Is it ours, or is it a world meant for another person or another time?

A version of this piece appeared in Furtherfield’s “News From Where We Are” podcast. Listen below.

Originals & Credits:

https://unsplash.com/photos/r2Mf3WFOVZc (Brian McGowan)

https://unsplash.com/photos/ykiDoi46Xjc (Brian McGowan)

https://unsplash.com/photos/m2hY9MLW7rU (Nick Bolton)

https://unsplash.com/photos/GTBevTmXTXo (John Cameron)

https://unsplash.com/photos/IEeqknvHRKQ (John Cameron)

https://unsplash.com/photos/OQWu-hk7pKo (Martin Sanchez)

https://unsplash.com/photos/cAnOxOnm_lg (Waldemar Brandt)

https://unsplash.com/photos/OBmBHmrc3pw (Anastasiia Chepinska)

https://unsplash.com/photos/LrEKYGwCo-k (G-R Mottez)

https://unsplash.com/photos/UXdDfd9ma-E (Victor He)

https://unsplash.com/photos/TcQx4jie4pg (Brian McGowan)

https://unsplash.com/photos/LNYdatC3znA (Martin Sanchez)

https://unsplash.com/photos/fUNCEHy4sZs (Tobias Rehbein)

https://unsplash.com/photos/WxRd7byFxs4 (Zach Vessels)

https://unsplash.com/photos/lWE2gVjdM-Q (Chloe Evans)

https://unsplash.com/photos/yo5wIVapll0 (Christine Sandu)

https://unsplash.com/photos/QHMn79tEp5E (Paul Merki)

https://unsplash.com/photos/ml3js226u48 (Thom Masat)

https://unsplash.com/photos/86Tyuh4cz8k (Martin Sanchez)

https://unsplash.com/photos/VwpvVCIExUE (Alin Luna)

https://unsplash.com/photos/fgvf4QgTn5Y (Erik Mclean)

https://unsplash.com/photos/qUb5Rkbdcq0 (Nathana Reboucas)

https://unsplash.com/photos/QtTKfb23nBc (Hello I'm Nik)

https://unsplash.com/photos/yvtSSxzgLI (Kseniia Llinykh)

https://unsplash.com/photos/GmWu4ZCP5PE (Nathan VanDeGraaf)

https://unsplash.com/photos/CEFYNiM9xLk (Luke Jones)

https://unsplash.com/photos/3oKxLPkhMtY (Markus Winkler)

https://unsplash.com/photos/yvxw4K9lYKo (Sarah Kilian)