The Anxiety of Smart Cities: How Technology Moves People

This article originally appeared in nextrends.

A window-sized LED display slowly shifts from darkness to an early-morning blue, waking you from your slumber on a Wednesday morning. After taking a shower and vigorously brushing your teeth, you review your presentation slides in an augmented mirror, and exit through the front door.

The year is 2045: your office arrives at 6:45am.

You see a few others pass by — megabuses, glass cubes with soft curves and wheels, and then your colleagues pull up in an elegant steel and glass dome, gathered around a wooden conference table. As you step into this mobile office, you look outside to see your own bedroom roll away in the opposite direction, toward a storage center for unused housing units where it will remain for the duration of your workday — revealing a massive public space where your neighborhood used to be. Tall, grid-like structures disassemble themselves as your neighbor’s homes descend and disperse, replaced by boutique clothing stores and fashionable hipster coffee shops surrounding a temporary playground and garden.

This is just one vision presented over the course of two events centered on the future of cities and mobility: a two-day designathon around Urban Swarm Behavior and a full-day Urban Tech Summit, both held for the swissnex Salon during the Zurich Meets San Francisco festival. By bringing together designers, urban planners and leaders from both the tech industry, community groups, and policymakers to imagine a world of the future, we can begin to think more critically — and inclusively — about the world we’re building today.

Here are some of the important speculative futures that can help us reimagine urban space.

THE MEGACITY IS A FUTURE IN MOTION

The most ambitious vision of the autonomous vehicle could be cast as a future of a self-driving everything. Today, the free movement of the digital nomad has already cultivated an infrastructure for remote work and a lifestyle of mobility: co-working spaces and room share services are just waiting to be paired with ride-share and public transit.

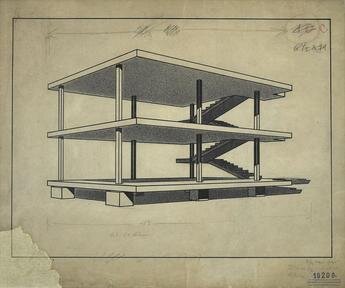

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier), 1914-15, Maison Dom-Ino (Dom-Ino House), drawing

With a rapid rise in urban populations and jobs concentrated in areas of highest population density (in other words, today’s San Francisco), distribution and allocation of space could drive the development of flex-space neighborhoods, where modular components can be assembled, stacked, and removed autonomously. Take the pop-up model, where businesses briefly occupy vacant commercial space; food carts, where restaurants arrive in parks or parking lots; or even San Francisco’s Tech Buses, mobile offices making the daily journey from San Francisco residences to corporate campuses in Mountain View or Palo Alto, with wi-fi and video conferencing.

Think of it as Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s Dom-Ino house writ large for the age of AI. Le Corbusier’s bold vision for post-war construction wasn’t constructed until 100 years after it was conceived, but stands monumental in the minds of architects nonetheless: the idea of a fundamental structure that can incorporate modular, customizable living space.

This overlaps with the concept of adaptable, flexible spaces created by storage containers — in resurgence in the US since at least 2003, when Adam Kalkin created the “Adriance House” out of 12 shipping containers in Blue Hill, Maine. Since then, projects have become so common that they have an entire industry dedicated to rentals for pop-ups, and are the basis of quick, savvy architectural solutions in everything from schools in South Africa to a removable FIFA stadium in Qatar. The step from transportation-container-homes to self-driving-container-homes seems obvious.

“Is a city built for passengers instead of residents truly a community?”

But so, too, are the constraints: this approach to a more efficient use of space requires constant motion, and constant motion is an inefficient use of energy. Such an approach is unlikely to be used for an entire urban spaces, but adoption in small commercial centers, empty lots, or tourist hubs could be on a close horizon. If it happens, it begs the question of what precisely the term “city center” even means: who can afford to live there, and is a city built for passengers instead of residents truly a community?

LANDMARKS BECOME CRUCIAL — OR DISAPPEAR

The French philosopher Frédéric Gros has written an entire book about the joy of walking: “You’re doing nothing when you walk, nothing but walking. But having nothing to do but walk makes it possible to recover the pure sensation of being, to rediscover the simple joy of existing, the joy that permeates the whole of childhood.”

Could a smart, augmented city somehow maintain this pleasure of presence and wandering?

As augmentation and AI assistance becomes “smarter” and more widely adopted, the easier it becomes for cities to solve today’s complex problems. Paradoxically, as cities become more complex, it requires more augmentation and AI assistance for humans to navigate and understand the problems of tomorrow. The simple joy of existing could easily get lost to those bursting announcements to turn left in 400 feet — wandering minds brought back to focus on the destination, and the apps to get you there, rather than the journey.

As our cities become “smarter,” augmented by layers of data and interfaces, they will likely become more aloof to simple navigation. Humans will lose much of their wayfinding ability, but we also risk eroding the joy of the wander, the serendipitous connections that bind humans together and give rise to the creative frictions of urban life. One of the challenges of adapting to the data-driven city is keeping the human at the center of its design and its systems, rather than requiring a machine to translate a distracting and complex environment back to them.

Try walking back from a location you’ve arrived at while staring at the GPS map on your phone: research has shown that divided attention during navigation reduces memory and connectedness to space. Creating systems that inspire knowledge and rootedness would become even more difficult if landmarks are in motion, or transforming themselves to meet different needs at different times of day.

Finding new ways to anchor our knowledge certainly creates new opportunities: apps that help us navigate through sounds, smells, emotions, and experiences may replace services that entirely off-load our navigation. Subtle tactical sensors such as vibrations indicating a direction, rather than requiring us to stare at a map, could inspire more presence in the city around us.

Already, we’ve seen apps that work to reverse this off-loading. Serendipitor, for example, helps to create memory anchors that can stimulate serendipity, adventure, and chance encounters in civic life, even as we stare at our phone to find our way to the market. Actual directions from Serendipitor include instructions such as, “Turn right toward 18th St and then find the nearest tree and sit under it for one minute. Take a photo.”

Minimalist navigation is also at the center of Crowsflight — a deliberately stripped-down navigation system that is, at its heart, an electronic compass. It points to the place you want to go, and leaves the path you take to get there up to you, encouraging exploration, distraction, and leisure.

BIG BROTHER BUYS A BAGEL

A visualization of San Francisco created from data of running paths. Created by Eric Fischer, CC-BY 2.0.

A frequent theme of the proposals presented (and discussions held) during the designathon was the evolution of the train ticket into a rewards system. Smart Card proposals typically involved some kind of tracking mechanism, such as a steps counter tied to GPS, which would help users earn points for responsible civic behavior: 100 points for walking 10,000 steps, for example. Smart systems might detect a user’s location and gently nudge them toward behaviors that help ease traffic and congestion, rather than contribute: a user on a main street at rush hour may get bonus points if they walk to a coffee shop 5 blocks away, to a less congested street, and grab a free coffee before hailing their ride-share car from a less congested neighborhood.

These cards would universalize access to public transit, constantly negotiating pricing between a network of ride-share systems, buses, trams, eScooters, bicycles, and pedestrian behaviors, with “good” behaviors (such as biking or walking) earning discounts toward “bad” ones (hailing a solitary taxi during rush hour). They’d also help drive traffic to local businesses that need customers or just have leftover danishes ready to sell at a discount. (There’s perks to artificial omniscience, and they come in the form of discount baked goods.)

But these systems require data, and personalization requires tracking. The personal disclosures required to participate in such a system are no less than 24 hour monitoring — and even predictive monitoring of people, regardless of whether they’ve even signed up. That still makes people nervous (though, given the 2.5 quintillion bytes of data humans generate every day, we may have already collectively agreed that we’re cool with it).

The worst case scenarios of all this data collection is already painfully evident — Hong Kong was pulling DNA data off of cigarette butts to reconstruct the faces of litterbugs and plastering them across billboards to shame them back in 2015, not 2150. The point cards for good behavior could tilt our desire for lighter traffic and smoother mass transit toward techno-dystopian authoritarianism rather quickly — especially without careful conversations about limits on data. The argument that we should take a few points away from people who don’t recycle is a dangerously appealing common-sense system, but the slipperiness of that slope should scare us.

The designathon and urban tech summit participants tackled the city of 2045, when cities are built on layers of data collected in public space, even from public services. But data from these systems may not be easy to tap for public benefits if we don’t work to encourage compatibility across data formats, and help the public participate in conversations about how all this data might be used — and whether or not our collective data is worth more than a cup of coffee.